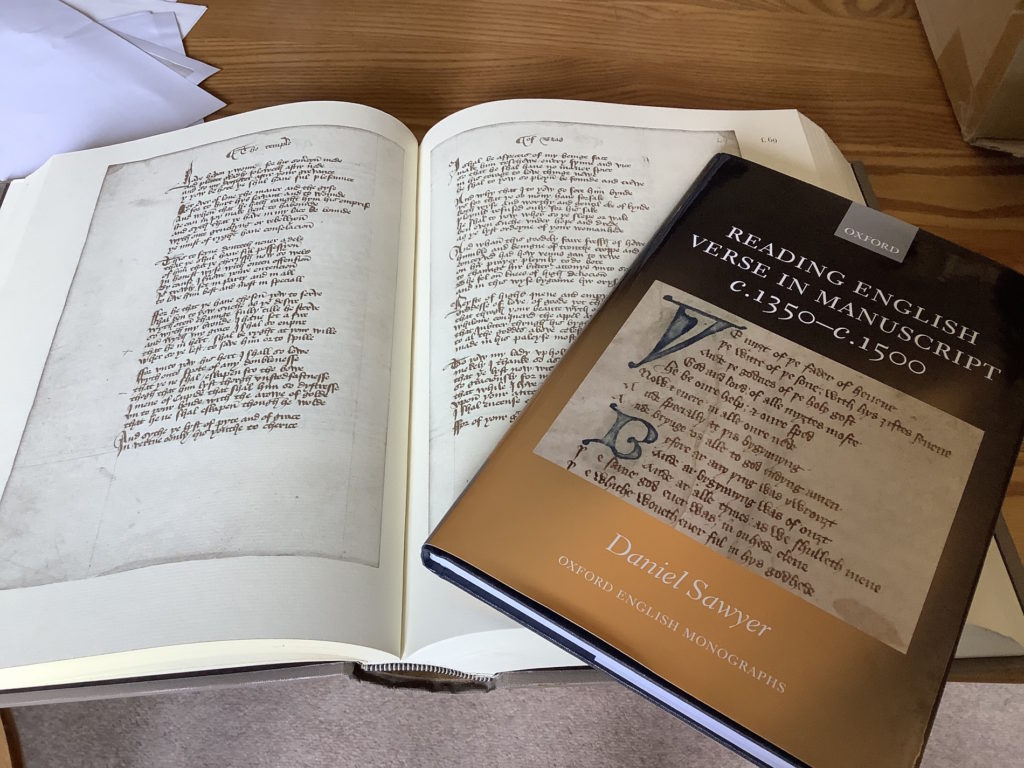

My new book was published this month. Reading English Verse in Manuscript c.1350–c.1500 can be ordered from OUP here, and, in the UK, at the time of writing, Blackwell’s are selling it for about £5 less.

This is in a sense ‘the book of the doctorate’, but it’s changed a great deal since I received my DPhil. The book is shorter, clearer and punchier. It draws on a significantly larger mass of evidence and corrects various errors and fuzzinesses in the doctoral work. And none of it has been published elsewhere: this is not a monograph whose most exciting chapter can be found as an earlier article.

Here is the blurb:

Reading English Verse in Manuscript c.1350–c.1500 is the first book-length history of reading for later Middle English poetry. While much past work in the history of reading has revolved around marginalia, this book consults a wider range of evidence, from the weights of books in medieval bindings to relationships between rhyme and syntax. It combines literary-critical close readings, detailed case studies of particular surviving codices, and systematic manuscript surveys drawing on continental European traditions of quantitative codicology to demonstrate the variety, vitality, and formal concerns visible in the reading of verse in this period.

The small-and large-scale formal features of poetry affected reading subtly but extensively, determining how readers might move through books and even shaping physical books themselves. Readers’ responses to one formal feature, rhyme, meanwhile, evince a habitual but therefore deep-rooted formalism which can support and enhance close readings today. Reading English Verse in Manuscript sheds fresh light on poets such as Geoffrey Chaucer, John Lydgate, and Thomas Hoccleve, but also shows how their works were read in manuscript in the context of a much larger mass of anonymous poems that influenced canonical poems, in a pattern of mutual influence.

It is, I’m sure, never easy to write any book, but I can certainly attest that it’s not easy as early-career researcher on a series of fixed-term contracts entailing duties other than writing the book. A global health crisis happening during the final stages of work doesn’t help, either!

It is true too that manuscript work often demands a kind of slow study. It might well be that in future I’ll grasp further insights from the evidence I gathered researching this book. There is a grand survey in there somewhere, with all its is dotted and all its ts crossed.

But there was also a book-shaped story to be told about the ways in which later Middle English verse was read, so, in the medium term, I decided to tell that story. I hope the book will broaden out and push forward the history of the reading of English in this period. Among other things, I hope it might prompt scholars to :

- Look further beyond readers’ marginalia for information about reading

- Be more ambitious in reconstructing the formalisms of past readers and writers (sometimes the two formalisms are distinct!)

- Consider how we sometimes ask material evidence to behave like textual evidence, rather than letting the two inform each other

- Attend more to traditions of quantitative manuscript study in several continental European languages.

- Read now-canonical Middle English poets with a firmer sense of the ties linking those poets to the greater mass of verse, much of it anonymous, which often now goes unread

Comments