The Chaucer Review has published my latest article, ‘Form, Time, and the “First English Sonnet”‘. You can find it on JSTOR or on Project Muse, or you can email me: I will be delighted to share a copy with anyone!

Here is the article’s abstract:

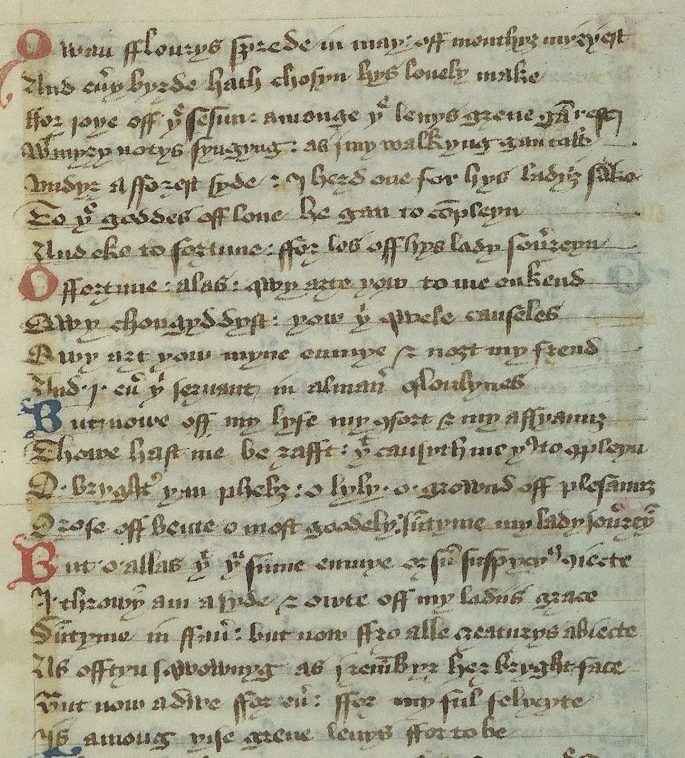

The earliest known English poem rhyming ababcdcdefefgg appears within John Metham’s 1448/9 romance Amoryus and Cleopes. Scholarship cannot, however, easily claim Metham’s lyric as the first English sonnet: contrary to past suggestions, available historical and manuscript evidence indicates that he did not intentionally create a sonnet, but rather composed in the form accidentally. This inset lyric’s rhyme scheme therefore represents, possibly uniquely in English, sonnet form without the sonnet tradition. Despite this isolation, however, attentive reading shows that the lyric achieves certain effects very like those produced by later English sonnets. The common features underpinning these effects even in a text not knowingly written as a sonnet might help criticism isolate factors that make up form’s essence or quiddity.

This article is unusual and strange, not unlike the poem it takes as its topic, and indeed not unlike the most odd romance, Amoryus and Cleopes, which transmits that poem. The inset lyric in question is transcribed, contextualised, read closely, and read in its relationship with the rest of the text. Towards the article’s end, I try to navigate through some issues in the way we think about form in general, in all periods and languages. I’m not at all suggesting that the piece achieves anything like a final word on the topic, but I hope it might be useful!

I ought to record here some addenda:

- In note 45, I point to two places in Chaucer where he appears to use through-rhyme to flatten out a pre-existing stanzaic rhyme pattern. I’m now wondering whether these instances in Chaucer might not be orthographically identical in surviving copies, but aurally distinct in probable pronunciation, given the etymologies of the words involved. More work to do there, then, for future writing: I’m drafting a piece on broken form in Chaucer in the light of the so-called ‘global turn’.

- Had it arrived on my desk in time, I’d have liked to fit in some engagement with Eric Weiskott’s new book, Meter and Modernity in English Verse.

- I wish I’d spotted, while writing, that line 1140 of Amoryus and Cleopes, just before the romance calls back to the last line of its inset lyric, is about happy atemporality.

It seems worth recording these, because doing so is responsible scholarship, because all research is really work-in-progress, and because modelling those first two becauses for our students is important!

Comments