I’ve just published a new article in postmedieval! It describes how pirates informally reproduced Jack Spicer’s long poem The Holy Grail in the 1960s; along…

Leave a CommentTag: codicology

Just out from me in Textual Practice, ‘Manuscript Canonicity‘: an article exploring how manuscripts themselves can generate prestige in present-day scholarship. This article’s published open access!…

Leave a Comment

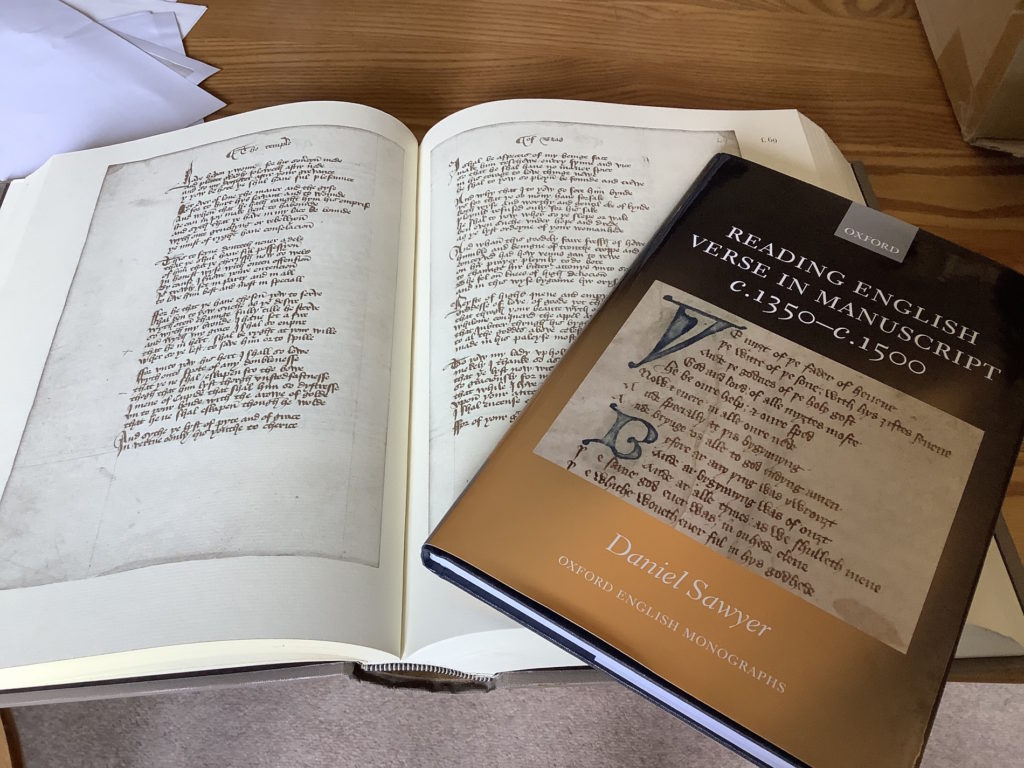

My new book was published this month. Reading English Verse in Manuscript c.1350–c.1500 can be ordered from OUP here, and, in the UK, at the time of writing, Blackwell’s are selling it for about £5 less.

This is in a sense ‘the book of the doctorate’, but it’s changed a great deal since I received my DPhil. The book is shorter, clearer and punchier. It draws on a significantly larger mass of evidence and corrects various errors and fuzzinesses in the doctoral work. And none of it has been published elsewhere: this is not a monograph whose most exciting chapter can be found as an earlier article.

Here is the blurb:

Leave a CommentI have a new article out, and a pretty weighty one too: at c.12,000 words, drawing on evidence of 1,511 (probably) lost medieval books gleaned…

Leave a Comment

Back in 2016 I had a chapter come out in the fine collection Spaces for Reading in Later Medieval England, edited by Mary Flannery and Carrie Griffin. So fine was the collection, in fact, that it was one of the most-downloaded books on Palgrave’s entire literature list (not just medieval literature!).

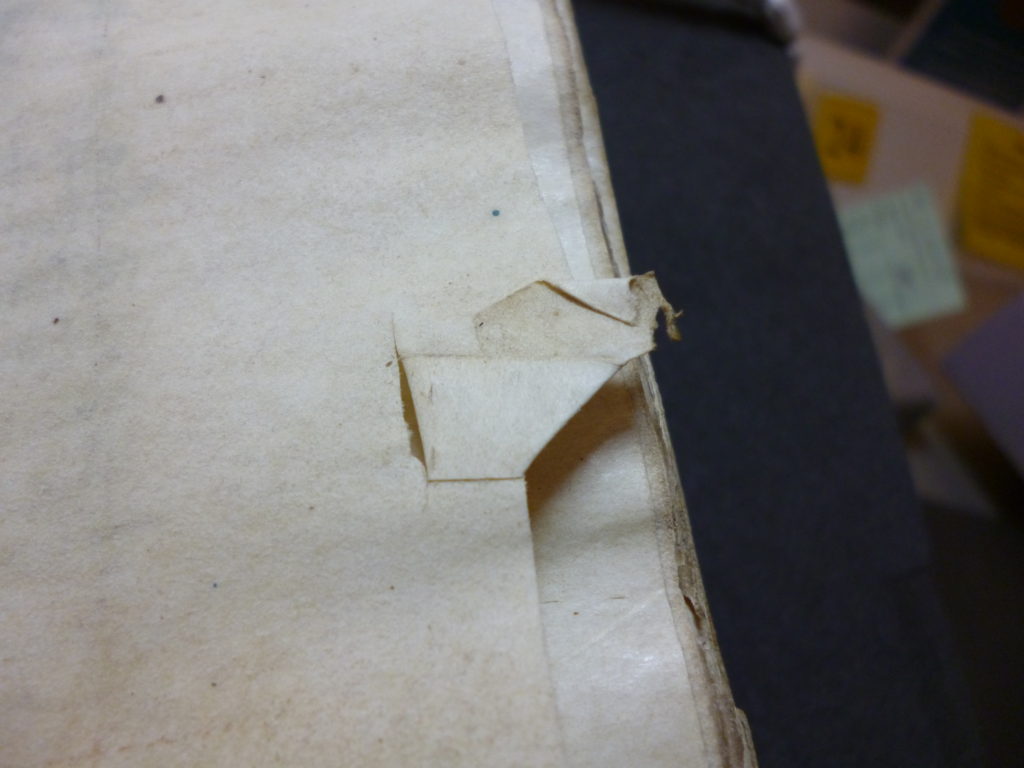

My chapter discussed how we might study the fixed physical bookmarks sometimes found in medieval manuscripts, turning them into evidence which might tell us something specific about reading. It was, to my knowledge, the first detailed exploration of the uses of these rather enigmatic markers.

I’m still pretty pleased with it, and especially with the distinction I suggest between bookmarks which reinforce textual structures and bookmarks which cut across those structures. But I’ve since had a further thought about this evidence, hence this blog post…

Leave a CommentThis is a trimmed and lightly edited version of a paper I gave in the Bodleian’s Weston Library in January 2019. I was asked to say something useful to graduate students across a range of humanities disciplines, and so I set out to demonstrate the potential interest of manuscripts which might seem to us to be normal and boring.

I think there might be some useful points made here, and I doubt I can publish it elsewhere, so I’m going to put it out as a blog post in case it might help anyone.

I’d like to look at a ‘dull’ or ‘mediocre’ later medieval English literary manuscript and bring out what might be interesting about it. Such manuscripts by no means the ugliest and messiest productions, but they’re also a long way from being the most luxurious, and they rarely receive attention.

It is (I think) by looking at seemingly dull, normal manuscripts that we might learn the most: normal manuscripts are the crucial context for the exceptional books which excite us, and normal manuscripts also let us study normality, a neglected topic in and of itself.

Let’s consider MS Laud Misc. 486. This book contains a copy of The Prick of Conscience, the most widely-witnessed medieval English poem. We usually ignore this text because of the sheer number of surviving copies and because of its content, which modern taste finds rebarbative. The poem is followed by a copy of Gregory the Great’s Cura Pastoralis by the same scribe.

The very brief online description of this manuscript would probably not excite us. But in fact the book offers many points of interest.

Leave a CommentI enjoyed speaking at the Digital Humanities at Oxford Summer School, and I hope the audience got something out of it! They were a kind, engaged set of listeners and they asked very useful questions. Those questions prompted this post.

In my session we looked at some objects from the Bodleian’s collections, handled ‘live’ in the lecture theatre by the brilliant Martin Kauffmann (Martin is the Bod’s Tolkien Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, and he’s both a formidably knowledgeable scholar in his own right and a great facilitator, the linchpin of much manuscript-based teaching). Among other things, we examined a couple of books of hours: one printed example, which both contains older woodblock prints and later manuscript material, and one in manuscript.

In one facet of my argument I emphasised how these books offer us much intimate and fascinating information despite being examples of one of the most ordinary and commonplace kinds of surviving book. In my conclusion I made a more general plea for attention to seemingly humdrum, ordinary objects in our research, whatever it is we’re researching.

Leave a CommentPrompted by the work I’m doing on the Wycliffite Bible project, I’m going to throw some thoughts at the wall and see if any stick.

Transcription is a significant part of the project work at the moment: an early step in the process of editing. In fact it’s how my first day started after an initial meeting and learning how to make a cup of tea in the faculty kitchen. Transcription was also a significant feature of my work for my DPhil thesis—I was handling, and sometimes quoting from, a lot of unpublished, unphotographed material. (Because if you work on the most successful English poem before print the rise of digital facsimiles hasn’t done much for access—but this is a topic for another time.)

Transcription’s a skill. We’re taught it, or have to teach ourselves, or muddle our way to grasping it through some combination of the two. On the MSt course here the palaeography exam requires you to transcribe and (roughly) date manuscripts from images. My interview for my current job began with a timed transcription test: how much of these two pages from different manuscripts can you transcribe accurately in ten minutes each? More broadly, transcription’s an activity which underpins editing and calendaring, or in other words it’s necessary for the things which are necessary for pretty a lot of the other work carried out by medievalists.

2 Comments