Back in 2016 I had a chapter come out in the fine collection Spaces for Reading in Later Medieval England, edited by Mary Flannery and Carrie Griffin. So fine was the collection, in fact, that it was one of the most-downloaded books on Palgrave’s entire literature list (not just medieval literature!).

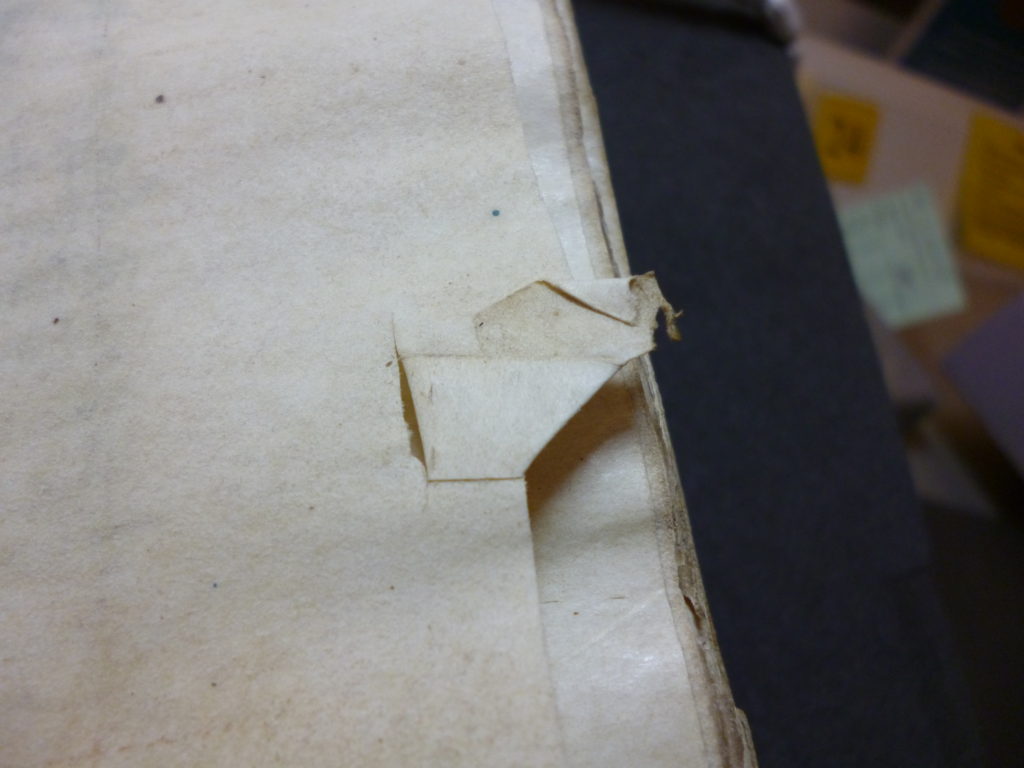

My chapter discussed how we might study the fixed physical bookmarks sometimes found in medieval manuscripts, turning them into evidence which might tell us something specific about reading. It was, to my knowledge, the first detailed exploration of the uses of these rather enigmatic markers.

I’m still pretty pleased with it, and especially with the distinction I suggest between bookmarks which reinforce textual structures and bookmarks which cut across those structures. But I’ve since had a further thought about this evidence, hence this blog post…

We think that reading and writing were separable skills in later medieval England. There must therefore have been a section of the reading population, size unknown, who were confident readers but not confident writers.

These non-writing readers would not have left marginalia reacting to the texts they read. They would, however, have been entirely capable of creating bookmarks.

We’ll probably never be able to work out whether any specific physical bookmark was created by a non-writing reader, but there’s a good chance that some of the physical bookmarks which survive are the work of non-writing readers. When we look at this evidence, we’re reaching beyond the section of the audience who could write.

I wish, of course, that I’d had this thought back when I wrote up my chapter! But that’s the nature of publication, I suppose: each item is, as one of my examiners comfortingly said to me before my doctoral viva, ‘a snapshot of the research’.

Fortunately, I have a brief section on fixed physical bookmarks in copies of some Middle English poems in my forthcoming monograph, so I can put the thought into print there. And it won’t be out of place: one of the methodological points made in my book (explicitly in the introduction, and implicitly throughout) is that we just don’t have many reactive textual marginalia attached to Middle English verse, and so our history of reading for this period of English literature must proceed by other means.

Fixed bookmarks in medieval manuscripts might be more enigmatic than marginal comments, but they’re also the handiwork of a broader audience.

Comments