I have a new publication out: a chapter in Book Parts, edited by Dennis Duncan and Adam Smyth. The collection as a whole considers the histories and uses of all the different components which go to make up a book. While the individual chapters draw on their authors’ research, they’re also relatively accessible, so as to serve undergraduates, new graduate students, and anyone else taking their first steps in book history.

My chapter considers foliation, pagination, signatures and catchwords: the interlocking systems which have quietly kept leaves in order since the advent of the early codex. They have different effects, and different audiences, and I enjoyed teasing out how we might think differently about each organisational approach. Given the tight word limit and the vast chronological coverage, it’s very possible that I managed to say something inadequate or just wrong. But I think my broader comments on the four leaf-marshalling systems are right, and I hope they will be generative too.

Along the way, I bring to light: previously un-discussed examples of representational catchwords in English manuscripts; evidence revealing that at least one later-medieval scribe could perceive the brown parchment surface of a page as conceptually blank/blanc; and the provocative topic of the ‘anticipated trimming’ of codices, that is, cases in which trimming was expected and approved by book producers. This last item might upend our standard stratigraphical model for distinguishing between historical accretion and modern subtraction from the book.

I close the chapter with some comments on the recent history of reading which I’ll briefly expand on here. In some ways, it seems to me, e-books are not a radical departure from the idea of ‘the book’, which was, as James Raven’s recent What is the History of the Book? shows, already an extremely capacious category. It is true that e-books make page-divisions highly unstable, but this is quite like the effect of dissemination by multiple scribes who wrote handwriting which took up different amounts of space—the very thing which makes secundo folio records useful in the first place.

The big change in the history of reading, I think, is the arrival of the feed, by which I mean anything which flows, such as your Facebook or Twitter timeline.

It is the feed, not the e-book, which has become globally successful: as I believe Naomi Baron noted in Words Onscreen, e-books have only taken off in a limited range of populations, and since Baron’s book was published (2015) there’s been more evidence that their popularity has plateaued. Almost everyone on the internet is reading feeds, meanwhile, and in some places—those places where Facebook provides a stripped-down version of net access largely filtered through, er, Facebook—the internet is the feed.

1999: there are millions of websites all hyperlinked together

2019: there are four websites, each filled with screenshots of the other three.— David Masad (@badnetworker) May 28, 2019

Relatively static web pages and e-books can be folded into the history of the book. But the feed is most unlike the book, or even (if you ask me) the margins of the book.

What the long-term indications of this shift will be, I’ve no idea. I’ve enjoyed using Twitter since 2008, but I don’t feel especially optimistic about the feed. After all, one could argue (and this is far from an original point) that the feed’s arrival in the history of reading has something to do with the politics of the mid- and late-2010s in a considerable number of countries.

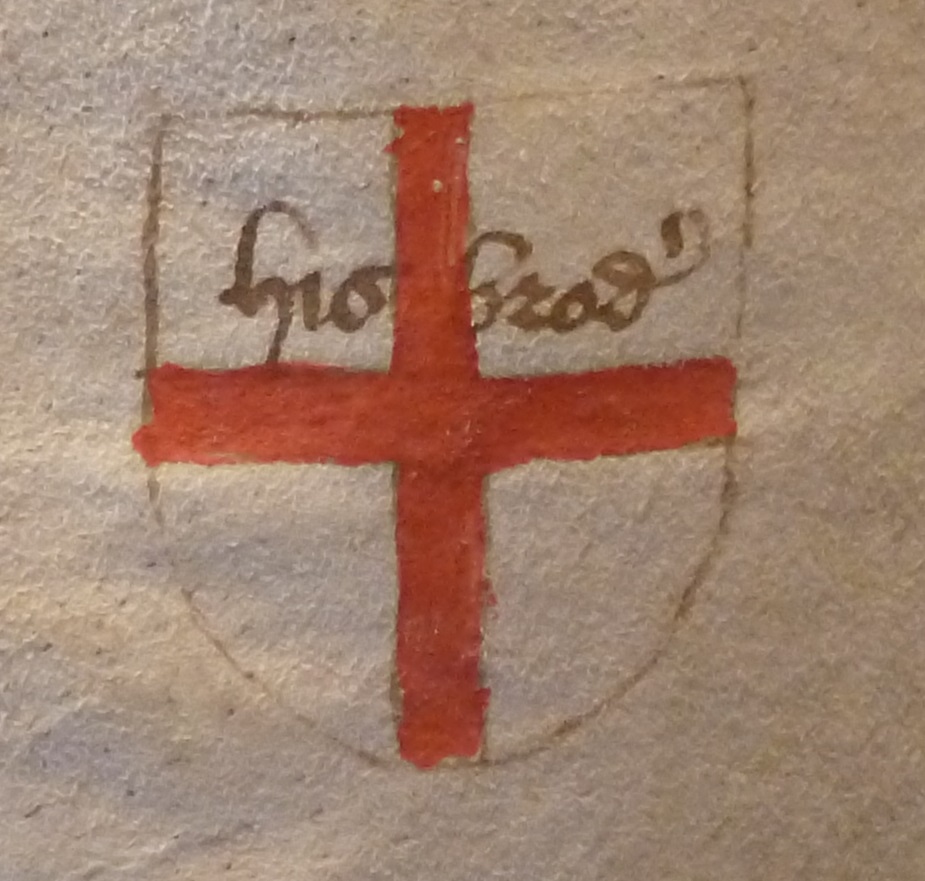

(The decorated catchword at the top of this post, by the way, comes from the description in the Middle English prose Brut of the 1120 sinking of the White Ship, which created a succession issue in England and, after the death of Henry I, a period of civil war.)

Comments